In the third chapter of James Clear’s book, Atomic Habits, he discussed habits and ways to build them. He starts the chapter with the story of a psychologist named Edward Thorndike who conducted an experiment that would lay the foundation for our understanding of how habits form and the rules that guide our behavior.

In his experiment, he placed each cat inside a device known as a puzzle box. The box was designed so that the cat could escape through a door “by some simple act, such as pulling at a loop of cord, pressing a lever, or stepping on a platform.” For example, one box contained a lever that, when pressed, would open a door on the side of the box. Once the door had been opened, the cat could dart out and run over to a bowl of food.

From his studies, Thorndike described the learning process by stating, “behaviors followed by satisfying consequences tend to be repeated and those that produce unpleasant consequences are less likely to be repeated.” His work provides the perfect starting point for discussing how habits form in our own lives.

Why your brain builds habits

A habit is a behavior that has been repeated enough times to become automatic. The process of habit formation begins with trial and error. Whenever you encounter a new situation in life, your brain has to make a decision.

Neurological activity in the brain is high during this period. You are carefully analyzing the situation and making conscious decisions about how to act. The brain is busy learning the most effective course of action. You’re feeling anxious, and you discover that going for a run calm you down.

There is a feedback loop behind all human behavior: try, fail, learn, try differently. With practice, the useless movements fade away and the useful actions get reinforced. That’s habit-forming.

As habits are created, the level of activity in the brain decreases. Because when a similar situation arises in the future, you know exactly what to look for.

Also, habits are mental shortcuts learned from experience. In a sense, a habit is just a memory of the steps you previously followed to solve a problem in the past. Habit formation is incredibly useful because the conscious mind is the bottleneck of the brain.

As a result, your brain is always working to preserve your conscious attention for whatever task is most essential. Habits reduce cognitive load and free up mental capacity, so you can allocate your attention to other tasks.

Note that habits do not restrict freedom. They create it. In fact, the people who don’t have their habits handled are often the ones with the least amount of freedom. Conversely, when you have your habits dialed in and the basics of life are handled and done, your mind is free to focus on new challenges and master the next set of problems. Building habits in the present allows you to do more of what you want in the future.

The science of how habits work

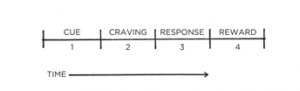

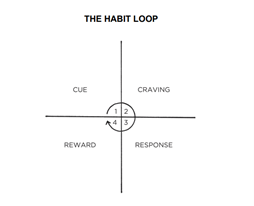

The process of building a habit can be divided into four simple steps: cue, craving, response, and reward. Breaking it down into these fundamental parts can help us understand what a habit is, how it works, and how to improve it.

This four-step pattern is the backbone of every habit, and your brain runs through these steps in the same order each time.

First, there is the cue. The cue triggers your brain to initiate a behavior. It is a bit of information that predicts a reward.

Your mind is continuously analyzing your internal and external environment for hints of where rewards are located. Because the cue is the first indication that we’re close to a reward, it naturally leads to a craving. Cravings are the second step, and they are the motivational force behind every habit. Without some level of motivation or desire— without craving a change—we have no reason to act. What you crave is not the habit itself but the change in state it delivers.

Cravings differ from person to person. In theory, any piece of information could trigger a craving, but in practice, people are not motivated by the same cues.

Cues are meaningless until they are interpreted. The thoughts, feelings, and emotions of the observer are what transform a cue into a craving.

The third step is the response. The response is the actual habit you perform, which can take the form of a thought or an action. Whether a response occurs depends on how motivated you are and how much friction is associated with the behavior. If a particular action requires more physical or mental effort than you are willing to expend, then you won’t do it. Your response also depends on your ability.

Finally, the response delivers a reward. Rewards are the end goal of every habit.

As mentioned, the cue is about noticing the reward. The craving is about wanting the reward. The response is about obtaining the reward. We chase rewards because they serve two purposes: 1. they satisfy us because they deliver contentment and relief from craving. 2. they teach us. Because rewards teach us which actions are worth remembering in the future.

If behavior is insufficient in any of the four stages, it will not become a habit. Eliminate the cue and your habit will never start. Reduce the craving and you won’t experience enough motivation to act. Make the behavior difficult and you won’t be able to do it. And if the reward fails to satisfy your desire, then you’ll have no reason to do it again in the future. Without the first three steps, a behavior will not occur. Without all four, a behavior will not be repeated.

The four stages of habit are best described as a feedback loop. They form an endless cycle that is running every moment you are alive. This “habit loop” is continually scanning the environment, predicting what will happen next, trying out different responses, and learning from the results.

Also, Clear splits these four steps into two phases: the problem phase and the solution phase. The problem phase includes the cue and the craving, and it is when you realize that something needs to change. The solution phase includes the response and the reward, and it is when you take action and achieve the change you desire.

The four laws of behavior change

Clear refers to this framework as the Four Laws of Behavior Change, and it provides a simple set of rules for creating good habits and breaking bad ones. You can think of each law as a lever that influences human behavior. When the levers are in the right positions, creating good habits is effortless. When they are in the wrong positions, it is nearly impossible.

He introduces 4 rules to create a good habit:

- The 1st law (Cue): Make it obvious.

- The 2nd law (Craving): Make it attractive.

- The 3rd law (Response): Make it easy.

- The 4th law (Reward): Make it satisfying.

We can invert these laws to learn how to break bad habits.

- Inversion of the 1st law (Cue): Make it invisible.

- Inversion of the 2nd law (Craving): Make it unattractive.

- Inversion of the 3rd law (Response): Make it difficult.

- Inversion of the 4th law (Reward): Make it unsatisfying.

These laws can be used no matter what challenge you are facing. There is no need for completely different strategies for each habit.

The key to creating good habits and breaking bad ones is to understand these fundamental laws and how to alter them to your specifications. Every goal is doomed to fail if it goes against the grain of human nature.

To sum up, a habit is a behavior that has been repeated enough times to become automatic. The ultimate purpose of habits is to solve the problems of life with as little energy and effort as possible. Any habit can be broken down into a feedback loop that involves four steps: cue, craving, response, and reward.

Also, you can use the Habitomic app to make useful habits for yourself based on these three steps. Well, why don’t you start right now?