Motivation is the process that initiates, guides, and maintains goal-oriented behaviors. It is what causes you to act, whether it is getting a glass of water to reduce thirst or reading a book to gain knowledge.

Motivation involves the biological, emotional, social, and cognitive forces that activate behavior. In everyday usage, the term “motivation” is frequently used to describe why a person does something. It is the driving force behind human actions.

B.J Fogg mentioned in his book, named Tiny Habits, about motivation. He says:

Motivation is a desire to do a specific behavior (eat spinach tonight) or a general class of behaviors (eat vegetables and other healthy foods each night).

He focuses on three sources of motivation: yourself (what you already want), a benefit or punishment you would receive by doing the action (the carrot and stick), and your context (e.g., all your friends are doing it).

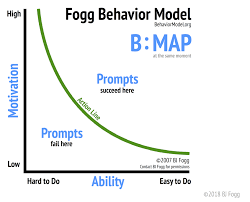

In Fogg’s Behavior Model, Behavior is a function of Motivation, Ability, and Prompt (B: MAP). In this conception, all behavior is instigated by a prompt, although that prompt may be internal (e.g. we know that when we are going to bed we should brush our teeth). If our combination of Motivation and Ability is above a threshold when the Prompt occurs (he calls the threshold the Action Line), we will do the behavior.

The clever thing about this model is that it takes the focus off of motivation as the key to changing behavior. Fogg suggests that rather than rely on motivation, we can explore the space of Ability and Prompts to change our behavior, and hence the Tiny Habits methodology. By designing clear prompts, and making the new behavior incredibly easy to do (low ability needed), we can make sure they happen even if the motivation is low. His canonical example is that when he had trouble flossing consistently, he started by flossing one tooth, and celebrating each day that he flossed one tooth (and sometimes flossing more when he felt like it).

Different types of motivation are frequently described by scientists and psychologists as being either extrinsic or intrinsic:

- Extrinsic motivations refer to behavior that is driven by external rewards. These rewards can be tangible, such as money or grades, or intangible, such as praise or fame. Unlike Intrinsic motivation, which arises from within the individual, extrinsic motivation is focused purely on outside rewards.

- Intrinsic motivations refer to behavior that is driven by internal rewards. In other words, the motivation to engage in a behavior arises from within the individual because it is naturally satisfying to you.

There are many different uses for motivation. It serves as a guiding force for all human behavior, but understanding how it works and the factors that may impact it can be important in many ways.

Understanding motivation can:

- Help improve the efficiency of people as they work toward goals

- Help people take action

- Encourage people to engage in health-oriented behaviors

- Help people avoid unhealthy or maladaptive behaviors such as risk-taking and addiction

- Help people feel more in control of their lives

- Improve overall well-being and happiness

Also, there are three major components of motivation: activation, persistence, and intensity

- Activation involves the decision to initiate a behavior.

- Persistence is the continued effort toward a goal even though obstacles may exist.

- Intensity can be seen in the concentration and vigor that go into pursuing a goal.

Causes of Having No Motivation

Sometimes, no motivation can be the problem. At other times, it’s merely the symptom of a bigger problem. Your motivation crested then came crashing down. And maybe you blamed yourself for not sustaining it. You’re not to blame. This is how motivation works in our lives.

B.J Fogg says that when you are prompted to act in a way that seems like a good idea, even a necessary one, you feel something. Whether you feel desire, excitement, or fear, it doesn’t matter—whatever is motivating the behavior will be quickly rationalized by your brain. It suddenly feels logical to do this thing that might be costly, time-consuming, physically demanding, or disruptive to our everyday lives.

We start from emotion, then find the rationale to act. Back in our prehistoric past on the savannah, this was a good thing. Motivating emotions evolved to help us succeed and survive. After all, you’d better have an automatic spike of fear that will make you run fast when you suddenly spot a lion.

He also talks about motivation fluctuation. He said that we also need to recognize that motivation changes on a smaller scale. It fluctuates day to day, even minute to minute, and we probably already know some of our predictable motivation shifts.

So, it’s important to take a few minutes to consider why you might have trouble motivating yourself. Here are some common reasons for a lack of motivation:

- Avoidance of discomfort. Whether you don’t want to feel bored when doing a mundane task, or you are trying to avoid feelings of frustration by dodging a tough challenge, sometimes a lack of motivation stems from a desire to avoid uncomfortable feelings.

- Self-doubt. When you think you can’t do something—or are convinced you can’t tolerate the distress associated with a certain task—you’ll likely struggle to get started.

- Being over-extended. When you have a lot going on in life, you’ll likely feel overwhelmed. And this feeling can zap your motivation.

- Mental health issues. A lack of motivation is a common symptom of depression. It can also be linked to other mental illnesses, like anxiety. So it’s important to consider whether your mental health may be affecting your motivation level.

If you don’t have the motivation, don’t worry. Here are some tips to help you to retake your motivation.

-

Argue the Opposite

When you’re struggling with motivation, you’ll likely come up with a long list of reasons why you shouldn’t take any action. So, try arguing the opposite. When you think you’re going to fail, argue all the reasons why you might succeed. Or when you think you can’t finish a job, list all the evidence that shows you’ll be able to complete the task.

Arguing the opposite can help you see both ends of the spectrum. It can also remind you that an overly pessimistic outcome isn’t completely accurate.

-

Practice Self-Compassion

You might think being hard on yourself is the key to getting motivated. But harsh self-criticism doesn’t work.

Research shows that self-compassion is much more motivating, especially when you are struggling with adversity.

So rather than beat yourself up for mistakes or call yourself names, create a kinder inner dialogue. Speak to yourself like a trusted friend.

-

Use the 10-Minute Rule

Permit yourself to quit a task after 10 minutes. When you reach the 10-minute mark, ask yourself if you want to keep going or quit. You’ll likely find that you have enough motivation to keep going.

-

Go For a Walk in Nature

Fresh air, a change of scenery, and a little exercise can do wonders for your motivation. Walking in nature—as opposed to a busy urban street—can be especially beneficial.

-

Pair a Dreaded Task With Something You Enjoy

Your emotions play a major role in your motivation level. If you’re sad, bored, lonely, or anxious, your desire to tackle a tough challenge or complete a tedious task will suffer.

Boost your mood by adding a little fun to something you’re not motivated to do. You’ll feel happier and you might even look forward to doing the task when it’s regularly paired with something fun.

-

Manage Your To-Do List

It’s tough to feel motivated when your to-do list is overwhelming. If you feel like there’s no hope in getting everything done, you might not try to do anything.

So as a solution, take a look at your to-do list, and determine if it’s too long. If so, get rid of tasks that aren’t essential.

See if other tasks can be moved to a different day. Prioritize the most important things on the list, and move those to the top.

-

Reward Yourself for Working

Create a small reward for yourself that you can earn for your hard work. You might find focusing on the reward helps you stay motivated to reach your goals.

Consider whether you are likely to be more motivated by smaller, more frequent rewards or a bigger reward for a complete job. You may want to experiment with a few different strategies until you discover an approach that works best for you. Make sure your rewards don’t sabotage your efforts, however.

-

Seek Professional Help

If your motivation remains low for two or more weeks, seek professional help. You may also want to seek help if your lack of motivation is affecting your daily functioning. Schedule an appointment with your physician. Your doctor may want to rule out physical health conditions that may be affecting your energy or mood.

-

Use Incentives Carefully

Researchers have found that rewarding people for doing things that they are already intrinsically motivated to do can backfire. Remember, intrinsic motivation arises from within the individual. It is essentially doing something for the pure enjoyment of it. Doing the task is its reward.

So be cautious with rewards. Incentives can work well to increase motivation to engage in an otherwise unappealing activity, but over-dependence upon such rewards might end up decreasing motivation in some cases.

-

Introduce Challenges

Challenge yourself. Sign up for a local marathon. Focus on improving your times or going just a little bit further than you usually do. No matter what your goal, adding incremental challenges can help you improve your skills, feel more motivated, and bring you one step closer to success.

-

Don’t Visualize Success

One of the most common tips for getting motivated is to simply visualize success, yet research suggests that this might be counterproductive. The problem is that people often visualize themselves achieving their goals, but skip over visualizing all the effort that goes into making those goals a reality. So do these tips:

- Instead of imagining yourself suddenly successful, imagine all the steps it will take to achieve that success.

- Knowing what you might encounter can make it easier to deal with when the time comes.

- Planning can leave you better prepared to overcome the difficulties you might face.

-

Take Control

One of the reasons people sometimes dislike “group work” is that they lose that individual sense of control and contribution.

So these are some solutions:

- If you are working in a group (or trying to motivate a group of followers), finding a way to make each person feel empowered and influential can help.

- Give individuals control over how they contribute to how their ideas are presented or used.

- Allow group members to determine what goals they wish to pursue.

Also, you can try these tips:

- Adjust your goals to focus on things that matter to you

- If you’re tackling something that is just too big or too overwhelming, break it up into smaller steps and try setting your sights on achieving that first step toward progress

- Improve your confidence

- Remind yourself about what you achieved in the past and where your strengths lie

- If there are things you feel insecure about, try working on making improvements in those areas so that you feel more skilled and capable.

Mr. Fogg also explained about two helpful exercises with examples in this regard.

First, he explained, behavior is something you can do right now or at another specific point in time.

These are actions that you can do at any given moment. In contrast, you can’t achieve an aspiration or outcome at any given moment. You cannot suddenly get better sleep. You can only achieve aspirations and outcomes over time if you execute the right specific behaviors.

Aspirations are abstract desires, like wanting your kids to succeed in school. Outcomes are more measurable, like getting straight as the second semester. Both of these are great places to start the process of Behavior Design. But aspirations and outcomes are not behavior.

In the first exercise, He’s going to define the aspiration for you: Get better sleep. In the second exercise, you’ll come up with your aspiration.

EXERCISE #1: A SHORTCUT FOR BEHAVIOR MATCHING

Step 1: Draw a cloud on a piece of paper.

Step 2: Write the aspiration “Get better sleep” inside the cloud.

Step 3: Come up with ten or more behaviors that would lead you to your aspiration of getting better sleep. Write each behavior outside the cloud with arrows pointing toward the cloud. You’ve now created your Swarm of Behaviors.

Step 4: Put a star by four or five behaviors that you believe would be highly effective in reaching your aspiration.

Step 5: Circle any effective behavior that you can easily get yourself to do. Be realistic.

Step 6: Find the behaviors that have both a star and a circle. Those are your Golden Behaviors.

Step 7: Design a way to make your Golden Behaviors a reality in your life. Do your best with this step.

EXERCISE #2: FOCUS MAPPING TO FIND GOLDEN BEHAVIORS

Pick your aspiration this time and use Focus Mapping (not stars and circles) to match yourself with the Golden Behaviors.

Step 1: Draw a cloud on a piece of paper.

Step 2: Write your aspiration inside the cloud. (If you can’t think of anything, write “Reduce my stress.”)

Step 3: Come up with ten or more behaviors that would lead you to your aspiration. Write each behavior outside the cloud with arrows pointing toward the cloud.

Step 4: Write each of the ten behaviors on a card or a small piece of paper. This is the first step in using Focus Mapping.

Step 5: Sort the behavior cards up and down along the impact dimension. Don’t think about feasibility. Focus on the impact that the behaviors could have.

Step 6: Slide the behavior cards side to side along the feasibility dimension. Be realistic. Can you really get yourself to do these behaviors?

Step 7: Look in the upper right-hand corner. Those are your Golden Behaviors. (If nothing is in this corner, go back to Step 3.)

Step 8: Design a way to make your Golden

In conclusion, everyone struggles with motivation issues at one time or another. Be kind to yourself, experiment with strategies that increase your motivation, and ask for help if you need it.